SAKATANI Yoshiko conducts a drawing class in the Yamashina area of Kyoto City. We interviewed her about the activities of the class since its founding in 1986.

──Today, it would be great if you could tell us about the series of events since the starting of Atelier Uoof

You’ve read the book that I wrote, haven’t you? Atelier Uoof Monogatari.(*1)

──Yes, I have. For some reason, the book is in our gallery. It’s quite a rare book isn’t it? The documented files, the collated information and such are all very clearly recorded.

That’s right, it’s all there. We can do editing via PC now but back then we didn’t have one so it was very time consuming. Copying this and that, and we did it all by hand. We probably made about 500 copies and ended up distributing them all. It was all meant for the students so that they would have something to remember, especially those who had dedicated their works towards exhibitions. There are those who could make such a thing much better now, but it certainly has the handmade quality to it, doesn’t it?

──It certainly does. It’s very charming both as a reading piece, and as a document piece.

What I found interesting was that the reason you initiated the class was because of the time when your friend’s child turned down the opportunity to join a drawing class, and you wanted to help him. I didn’t realise how long your commitment had been, from that time until now.

Yes, a relatively small thing that began it all. That child even still comes to my class. Actually, the mother of the child was a classmate of mine, she took her child to a nearby drawing class but they were hesitant to accept them; I think the teacher of the class probably didn’t know what to do with her. The mother knew that I had a part-time job at a drawing class while I was a university student, so she asked if I might be interested in starting a class myself. That was the impetus for how I started, and with that particular child as the start I ended up with about 6 children in total, half of them with disabilities. The place I began teaching at was also small. I have known the children for 3-4 years now.

──How you chose the location for class room is very interesting.

My first thing I did was not to start searching for a place, instead I went to seek advice from an elementary school teacher near to where I live. This teacher promoted the idea of making classes for disabled children just like normal classes. Back then it was still being discussed about whether disabled children should study separately, or together with other children. They live in their own property and they kindly offered me one of their spare rooms to use as a classroom. The building was actually under planning to be demolished within a year or so, but that place was our starting point.

──So the class room was an average residential apartment, right?

That’s right, a space with a couple of rooms. They didn’t mind the room getting messy. Towards to the end, just before the demolishment, we all were allowed to draw things on the walls and on the fusuma, the Japanese sliding doors. We had such a great time.

After that, we rented a space from a kindergarten and so on, and finally we found our place within a temple. It was the annex of the Higashi Honganji Temple. In there, I heard that there was a class for calligraphy, so I walked in and asked for a place for my own class. I was young and brave back then. The space I received for the class was a corridor that ran around the main body of the temple.

── Was it quite a spacious corridor then?

Yes, it was, it was about the right size to protect from rain showers. I was offered to use of the area once a week and I was allowed to use the space after placing down a large disposable sheet. Because we didn’t have any desks, I let my students simply draw on the floor. They were elementary school kids and they all enjoyed it that way, they seemed to have fun trying to avoid the rain drops.

──Did you let the children draw whatever they liked?

That’s right. In the beginning, I used to provide a theme for the drawings, but it seemed to lack any real sense of unity so I just let it be. If someone likes a rabbit, then keep drawing a rabbit. For the part time job I took when I was a student, I was the assistant to a teacher and was following a curriculum. I tried doing something similar, but it wasn’t really what I wanted. After all, kids are all different with or without disabilities, so I stopped making things based on a cookie-cutter design. Sometimes, I say, ”Let’s draw flowers because it is Spring” or “Let’s draw rain because it’s raining”… very random ideas overall, but in principal theme is free.

── At this time, did everyone take their work home with them?

Yes, back then everyone had their own sketch books which they worked on, so they used to take them back home. Eventually, the sketch books sneakily began to end up staying in the temple’s storage room. I hope they didn’t mind this!

──How long did you end up using the temple as a classroom space?

I can’t be sure, but let’s say it was about 4 years.

After we moved out of the temple, we relocated ourselves to my parents store room after having it renovated. Since then, we could stock tools and canvases there, and we started on oil paintings. Mr. Uni (Uni Hidehiro, a recording writer of this archive program) was especially into oil painting.

──Was Mr. Uni not particularly interested in paintings before starting oil painting?

When he was drawing at the temple, everything was such a mess. Drawings went beyond the borders of the sketch book, he was off somewhere as temple is usually a full of hiding spots. When we kicked off the start of oil painting, things were so much better. Probably as the size of the work gets bigger, he must love it more and more. From that time, Ms. Usami and Ms. Okochi and a few others showed their interest and continued working on it. Oil painting requires energy and patience, so it wasn’t a one off.

──Back then, how was the situation for supporting people with disabilities through art activities?

That was the time that Tanpopo-No-Ye had begun the movement called Able Art Kinki, and as a result many followed after that. It was after I opened my class. I actually didn’t have such policies at the time, and I was only motivated by the kids that I mentioned earlier.

──In Kyoto, there was Mizunoki Painting Class right?

Right, right, that one was the pioneer.

──Also, were there any other activities that inspired you?

Terms like Art Brut and Outsider Art were introduced for people with disabilities, so we joined in with those events in Tokyo and so on. Through these kinds of events, I met with Mr. HATTORI Tadashi(*2) and Ms. HATA Yoshiko(*3) of the Suzukake Painting Club. When our students' works were exhibited at “Kyoto Totteoki no Geijutsusai” (a project with open applications run by Kyoto Prefecture since 1995), it was Mr. Nishigaki(*4) of Mizunoki Painting Class who gave awards to many of my students, and at that time he told me that “the best way of teaching is to let it be, don’t teach them,” and it was then that I was assured that what I had done was the right thing

──Looking at your record, you had a joint exhibition with Kusakabe Art Class well, didn’t you? They were probably a similar figure to you in Kyoto, I presume?

We had a time where we were being called “Uoof of the East” and “Kusakabe Art Class of the West” within in Kyoto. Kusakabe Art Class is much bigger than ours and the teacher himself is an artist.

──The only similar point is that we are also not a welfare facility, that we are an art class that is open for everyone, with or without disabilities.

Mr. Kusakabe is also the type of person who isn’t too serious about it. If you are too serious, you may find it difficult to continue. What I get involved, it’s just purely art, not a personal matter. My part is just to provide a space for the art and to feel the enjoyment, it’s as simple as that.

In the beginning, I received many different kinds of advice, that I should be doing clay activities to support the drawing, and that way it would be more appropriate as an art class. However I didn’t have that in mind, I simply wanted to provide a space for stress relief. In your real life, you struggle, but in your art work, you can be discipline-free. So if anyone wants to stick to the same color or the same objects, then it’s totally fine by me.

I presume the families of the students at my class were not so sure, though, as everyone isn’t necessarily into art. We used to open our gallery in a supermarket, SEIYU, in Yamashina every year. Eventually, people come for their shopping and then popped in there and saw their art for the first time. The reaction was “What is this?!”, as if they hadn’t seen anything like it before. I wasn’t particularly ambitious, but I was just happy as long as we evolved.

──I heard that you paid attention to how you presented works made by people with disabilities and those without.

Yes, I did. I write their name by artworks, but that makes it complicated when they all get to the 2nd grade at elementary school, so I displayed just their name and not their grade or age. However, the works made by people with disabilities are quite different, so I am often asked how old the artists are. That’s the important difference.

Also, that wasn’t my own strict policy, it was more so from their family’s thoughts and ideas. The elements of art made by people with disabilities are usually highlighted when it is posted in the newspaper. Some people do object to it, but others not so much. I was really protecting them from the publicity. Nowadays, we are sort of “open” about who we are to the public, but 20-30 years ago, it was a different story. We had to be absolutely sure before we could choose to expose ourselves. Some people don’t react to us very nicely, so we have to face that, too. Even now, with any interviews I undertake, I often ask them to focus on their works and not so much on the personal details of the artists.

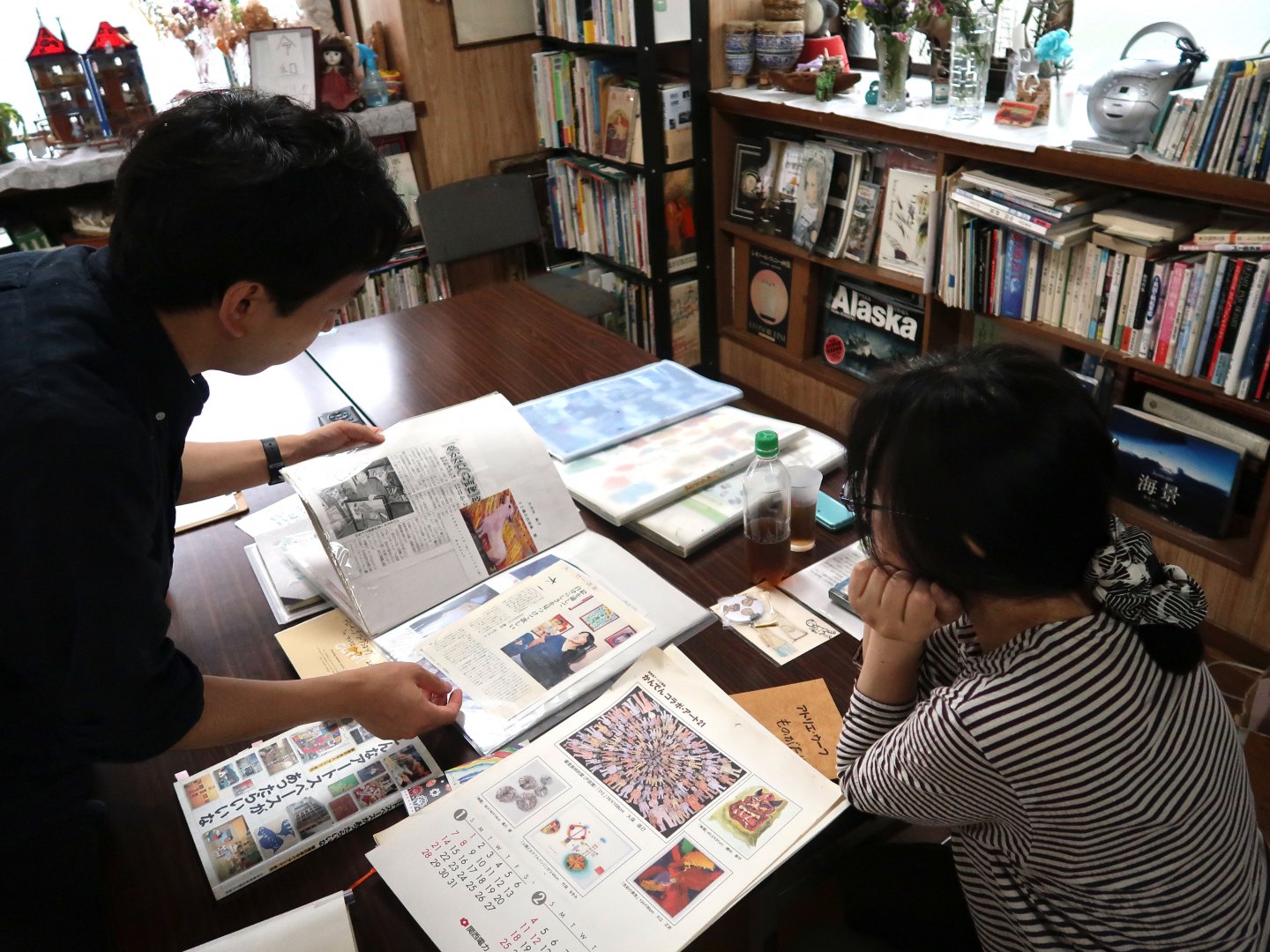

──You keep documents including various articles from those days, right?

There were so many articles in the early times. A lot of media coverage took place each time.

──Does that mean there were not so many other activities of this kind at the time?

I am not sure. The Museum of Kyoto asked us if we wanted to hold an exhibition. In 2000, we organized an exhibition called “katarikakeru-e” (pictures talking to us). We also participated in the exhibition, “nishikarakita-yuseitachi” (fairies coming from the West) which was held in Tochigi Prefecture.

──You stated in your book that you first thought that paintings drawn by people with disabilities were like those drawn by children, but noticed that in some ways they were different. Could you tell us more about this comment?

Children, of course, grow up, and their painting skills develop during their teenage years regardless of whether they have disabilities or not. Paintings done by children without disabilities become more like the ones drawn by adults in ten years time. However, paintings made by people with disabilities tend to show something wild, different and strictly straight, different from the ways that people typically learn. But, their paintings still develop by themselves. As you get used to drawing, you will eventually get a sense of color, and will gain confidence, and learn something like the joy of drawing. So, in the beginning, I discovered something new every day, and since I was young I was having a lot of fun doing it while being inspired by their pictures.

──How many people are currently coming to your classes?

There are about 30 members right now, but members don’t necessarily attend every time. So, about 10 people come to the class each day. Some come weekly, some monthly. The classes are held every Saturday from 10am to 4 pm. In the past, high school students and junior high school students came, and didn't leave until 7:00 pm or 8:00 pm. They spent time together here, reading manga and leisurely talking to each other. Nowadays, when they become junior high school students, they become busier and end up not being able to attend.

──I think it's good to have children with and without disabilities working together. Is there anything that you find difficult, or particularly good about it?

From the beginning, there has been no sense of discomfort at all. There aren't any particular problems. I think little kids might tend to think that they are like strange older brothers, but no one says it directly, and I think it's quite amazing. They are not particularly intimate, they're just in the same space at the same, but there's no real pressure to be particularly friendly. I leave it to them.

However, one issue is the sounds. What I'm worried about right now is that when small children, such as first graders, gather together, their voices are high pitched and they move so fast. Older children dislike loud noises, but they can't directly say that it's too noisy, so they panic and crush their pictures. In such cases, I have no choice but to say “sorry” and hug them. After a while they begin to calm down, but I cannot say to the small children not to come. That's why I say to both of them “hold on”. I guess this works out somehow.

At first, I was trying to divide attendees up by their age, children in the morning and older children in the afternoon. But they ended up not following this rule. I think I have been able to continue doing this because I’m not so strict. However, small children eventually grow up right? They remain naughty until the second grade of elementary school, and they can’t really stop once they start playing, but within one year or so they will begin to understand the situation.

*1 Atelier Uoof Monogatari (Published: 1999, text, edited, published by Ms. SAKATANI Yoshiko

*2 Mr. HATTORI Tadashi - Professor, Faculty of Letters, Konan University. He conducts research and exhibition planning on Outsider Art, Art Brut, and creative activities for people with disabilities and so on.

*3 Ms. HATA Yoshiko - Picture book writer, art director of "Borderless Art Gallery NO-MA" (Omihachiman City), and head of the Suzukake Painting Club.

*4 Mr. NISHIGAKI Chuichi - 1912-2000. Painter. After being an associate professor at the Kyoto City Technical School of Painting (now Kyoto City University of Arts) (1943-1949) and a high school teacher, he practiced art education for people with intellectual disabilities at the Mizunoki Residence (now Mizunoki) since 1964.

*5 Kusakabe Art Class - Presided by painter Mr. KUSAKABE Naoki. Since its founding in 1985, it has been accepting students with and without disabilities.

Interviewer: IMAMURA Ryosuke, FUNATO Ayako

Profile

UNI Hidehiro

UNI Hidehiro became a member of Atelier Uoof when he was a junior high school student. Back then, his pictures often did not fit on the small sheets of papers he used; instead they became three-dimensional, cut up, pasted and put together. Soon he showed his talent in oil painting. Drawing a horizontal line in the canvas produces an image in him, which feature dynamic composition and youthful and surreal color palettes. He continues his creative work at his own pace at Atelier Uoof as well.