Hattori Tadashi

Konan University Faculty of Letters

We are living in an era when everything is documented in lasting form. I may recall that I had an e-mail exchange with someone on a given topic five years ago, and by searching the e-mail history on my computer, I can instantly trace the whole conversation in chronological order and know what was said and when. This could not be accomplished with telephone calls and letters. At the same time, this is an era when many things go undocumented. In September 2019 a significant bureaucratic decision was made behind closed doors, one with major and lasting repercussions for freedom of expression and cultural support for public institutions in Japan, but evidently there are no minutes of the meeting or any data whatsoever documenting what led to this decision. Precisely because today all data is constantly recorded and stored, the powers that be carefully and thoroughly conceal information that might reflect negatively on them. Today, not leaving a record requires clear and specific intent. Unless I intentionally delete them, all the e-mails I have sent and received are preserved indefinitely.

Not long ago, it was a different story. Keeping detailed records required strong will and enormous effort, so it was common practice to examine data carefully and determine what needed preserving and what did not. Art exhibitions were relatively well documented and preserved, and looking through the annals of art institutions, one can find the artists and titles of works for all major pre-World War II group exhibitions, as well as lists of works from well-known artists’ solo exhibitions. It is fair to say this was only possible because the total number of exhibitions was much smaller then. Today, diverse exhibitions of varying sizes are held every day in all sorts of venues, and the pace of change is so fast that many exhibitions go almost undocumented. Even today, it takes considerable effort to create records of analog exchanges, such as the physical movement of works, as opposed to digital interactions like e-mail. Thus the exhibition history of a certain artist may be impossible to trace completely, or the record of a certain work’s being exhibited or lent out may be unclear. This is not often the case with the collections of public art museums, but it is commonplace for social welfare establishments serving people with disabilities, where works are not handled as rigorously as at museums. I may remember that a particular work was shown in an exhibition about five years ago, but find that no record exists of what kind of exhibition it was and how the work came to be included.

These observations may provoke one or more of the following reactions: (1) So what’s wrong with that? And (2) Isn’t it unreasonable to expect such scrupulous documentation? As for the former, I would respond that nobody can foresee the future of a work or an artist. A collector may come along and want to purchase work. As is common practice among art collectors, they may ask about the work’s past exhibition history, and in some cases may request works that have never been exhibited before. Or the creator may become famous, hold solo exhibitions and be the sole subject of art books. Editors will want to know the exhibition history of each work and to include a list of all the artist’s previous exhibitions, in line with the norms of book publication, and will expect social welfare establishments to provide that data as a matter of course.

Here we run up against the second reaction, that keeping such detailed records is impossible. This is certainly true, and I do not intend to accuse social welfare establishments’ administrators of laziness. The objective of creative activities at these establishments is to better the lives of attendees, and this takes on various dimensions and goals such as promoting independent decision-making and self-esteem, increasing opportunities for participation in society, and exploring possibilities for labor and income. This means that raising the potential value of a work of art by keeping accurate records serves these purposes in a broad sense, but it ends up being a somewhat low priority because there are so many things establishments can do to support attendees more directly. Also, there are not necessarily sufficient human resources to assign to all of these tasks.

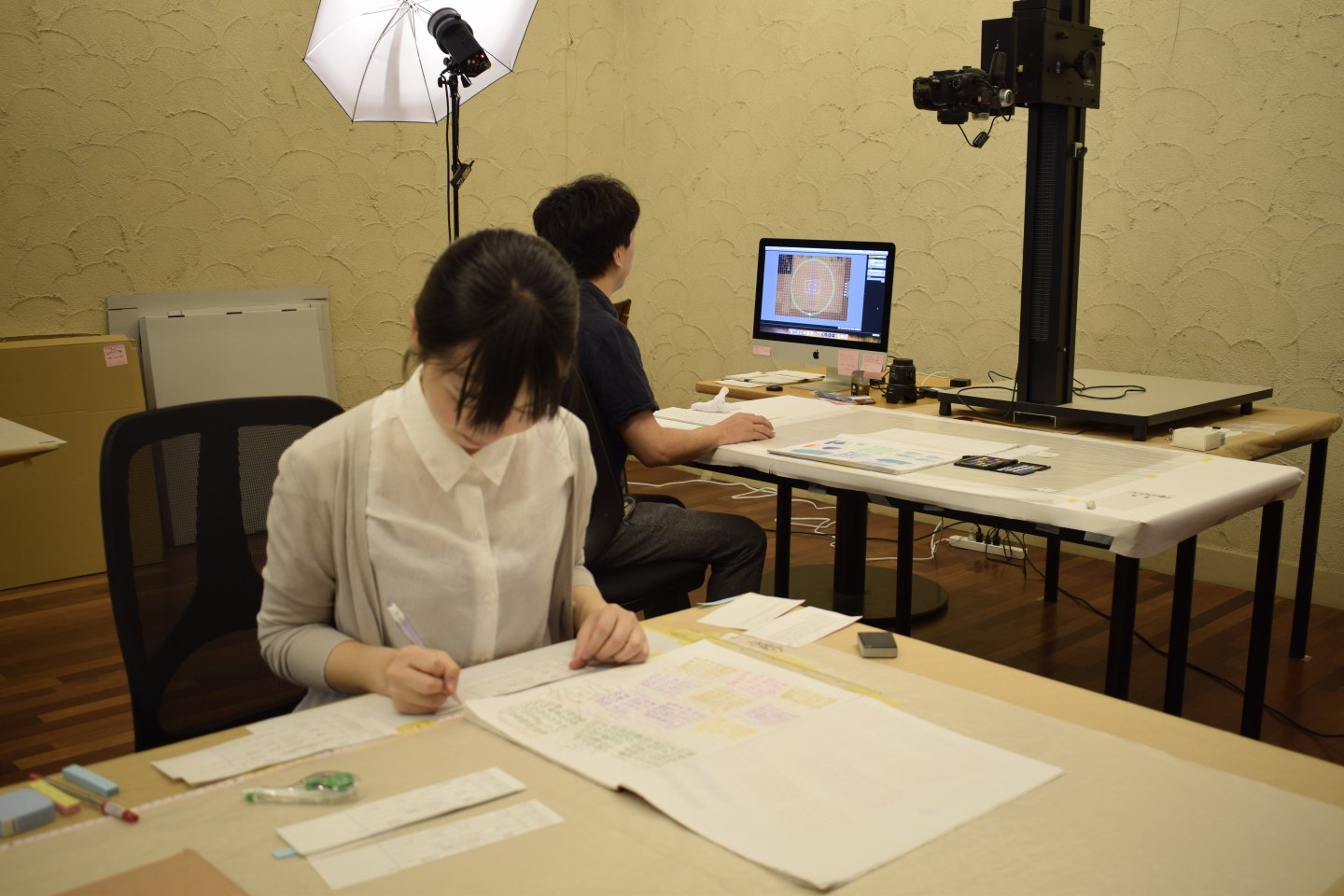

This makes the work of intermediary organizations such as the Kyoto Culture and Art Promotion Organization for People with Disabilities all the more important. Scrupulously keeping track of works, systematically organizing and managing them, is too great a challenge for most social welfare establishments to handle on their own. For this reason, a system in which third-party groups organize, manage, and publish records in cooperation with social welfare establishments can create an optimum environment for establishments, artists, and works. Such systems are still in the trial stages, but the concept is that social welfare establishments and exhibition planners convey unorganized raw data to an archiving project coordinator, and the coordinator classifies and organizes it as a database that can easily be searched and browsed. Art appreciators and exhibition organizers have free access to this information and can use it to inform establishments of their desire to purchase works, or to plan exhibitions. In the long run, these activities will have a positive impact on attendees’ self-esteem and participation in society. Expectations are high for such an environment for effectively and appropriately circulating works of art throughout society, as public property, to be realized in Kyoto in the near future. I believe this can be a significant step towards an inclusive society.

Shokaen Social Welfare Corporation Mizunoki, located in Kameoka City, Kyoto, is a pioneering establishment in this field, and has been facilitating creative activities since 1964. The Nihonga (modern Japanese-style) painter Nishigaki Chuichi (1912-2000) taught a painting class that drew attention from the art world in the early 1990s, and works produced there were featured in the Setagaya Art Museum exhibition Outsider Art of Japan (1993), one of the first shows in Japan of art by persons with intellectual disabilities. In 1994, 32 works by six Mizunoki-affiliated artists became the first from Japan acquired by the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland.

However, there are no works from Mizunoki, unquestionably one of the foremost facilities in Kyoto in terms of art by people with disabilities, in the above-mentioned archive. This is not due to administrators’ negligence, but to the fact that Mizunoki has its own archive. Unfortunately Mizunoki’s archive is not publicly accessible on the Internet, and opportunities to view its contents, such as exhibitions at the Mizunoki Museum of Art, Kameoka operated by Mizunoki, are extremely limited. Eventually, though, there will surely come a day when the Mizunoki archive, said to number about 20,000 works, is organized and made public. When it is, we can expect that the Kyoto Archive of Art by People with Disabilities will link to it, making it more widely accessible. This is a highly promising project model, and in fact this model has already been partially realized in the form of links from the Kyoto archive to Social Welfare Corporation Asaka Aiikuen in Fukushima Prefecture and Social Welfare Corporation Sojukai in Fukuyama City.

As mentioned earlier, it is difficult for social welfare establishments facilitating creative activities to create their own art archives, and indeed it is not easy for them to organize art exhibitions in the first place. This is because the skills and knowledge required to do so are completely different from those generally expected of staff at these establishments. With regard to creative activities by people with disabilities, which have grown more prevalent in Japan in recent years, it is often impossible for social welfare establishments to perform all the related tasks of providing the space, tools and opportunities to output works of art, storing and organizing them, planning exhibitions, and carrying out related publishing activities. The same is true of local government bodies that facilitate cultural and artistic activities for people with disabilities. In Western countries, many well-known studios for people with disabilities are adjoined by gallery spaces that exhibit, store, and sell their works, but studio and gallery are often operated by separate staff teams. This is only natural, since the skills required are different. Mizunoki is capable of building its own archive because it has established the Mizunoki Museum of Art, Kameoka, and can keep custody of the works as an organization independent of the social welfare establishment directly providing support to attendees. There are certainly other social welfare corporations and establishments with the necessary physical capabilities and motivation in Japan, and one hopes their number will increase, as this will promote artistic activities by people with disabilities. The Kyoto Archive of Art by People with Disabilities will surely serve as a model for such facilities as they embark on their own archiving projects. Meanwhile, for small studios that have difficulty archiving works on their own, it would be ideal if the Kyoto Archive of Art by People with Disabilities and art space co-jin could actively take charge of data management and exhibition of works. The activities of the Kyoto Archive of Art by People with Disabilities thus far demonstrate that it is possible to make up for staff shortages by actively utilizing external human resources, such as museum officials and artists, rather than forcing the limited staff of small establishments to do everything themselves.

One might dare to dream of this model spreading throughout Japan. Eventually, the archives of major social welfare corporations and establishments around the country and the archives of intermediary organizations supported by local governments may be organically linked, forming a giant network that makes it possible to browse and search for works by people with disabilities on a nationwide scale. This is something not even Japan’s six national museums have been able to achieve. It may be that here in front of our computer screens, viewing what is still a modest archive, we may in fact stand at the gateway of a vast dream to be realized in the future.

Hattori Tadashi

Professor, Konan University Faculty of Letters

Born 1967 in Hyogo Prefecture. After serving as curator at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art and the Yokoo Tadanori Museum of Contemporary Art, he was appointed Associate Professor in the Faculty of Letters at Konan University in 2013, and Professor in 2019.

Hattori is also engaged in research and organization of exhibitions relating to outsider art, art brut, and the creative activities of people with disabilities.

His published books include Outsider Art (Kobunsha Shinsho, 2003), Yamashita Kiyoshi and Art of the Showa Era (co-author) (University of Nagoya Press, 2014), Creative Activities of People with disabilities (author/editor) (Airi, 2016), and Adolf Wolfli: A Kingdom of 25,000 Pages (editorial supervisor) (Kokusho Kankokai, 2017).